Understanding the Constitution #8: The Framers Didn't Want Political Parties

"If I could not to go heaven but with a party, I would not go there at all."

- Thomas Jefferson to Francis Hopkinson, March 13, 1789

Given party politics today, which (to corrupt a phrase from Thomas Hobbes) is nasty, brutish, but definitely not short, one wonders what the framers of the Constitution were thinking. Actually, they were not. For good or ill - and mostly for both - they did not contemplate organized political parties. In fact, as Jefferson's quote put it, "party" was a repulsive idea.

"Party" to the framers bore no resemblance to today's political parties."Party" was understood as a self-interested group that James Madison characterized in Federalist #10, as adverse "to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community." No wonder the framers didn't like them.

Yet, Jefferson and Madison created the first political party. What they abhorred in theory, they decided they needed in practice. When Washington, at the recommendation of Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, approved of a national bank, the Virginians went ballistic. This was the strong national government they feared, so in 1791 they traveled through New York and New England searching for political allies and a way to organize them. Their efforts produced the Republican Party (not today's GOP).

It was sufficiently organized across multiple states by 1800 to give Jefferson the presidency against a weaker Federalist party. So, did parties live up to the framers' fears, or were they a needed if unwelcome development? Yes, and yes.

As long as Washington was president, political parties did not challenge him. Who would? But when he stepped down, the divisions between Federalists and Republicans took electoral form. The former favored a strong national government; the latter a weak one. Federalists pushed a commercial, manufacturing economy. Republicans believed an agrarian economy essential to freedom.

In the election of 1796, John Adams (Washington's vice-president) beat Jefferson by three electoral votes. According to the Constitution (which had not thought of political parties), as the second highest vote-getter, Jefferson became vice-president. This politically opposed pairing did not go well. (This was corrected with the 12th Amendment (1804), assuring future presidents and vice-presidents come from the same party.)

Political parties, even if no one wanted them, ensure the executive branch has an electoral mandate, a unified focus, consistency in policy and energy in administration. Parties thus permit accountability - not just in the presidency but in Congress. That's a plus, and not the only one.

Biographer Richard Brookheiser rightly labels Madison the "father of American politics." The strength of our system, Madison understood, is the opposition of ideas to ensure robust thinking. Political parties also inform and provide a vehicle for public opinion. The founding generation of "gentlemen" believed voters should be heard only at the polls, leaving daily government to the winners. Madison saw this flaw, and in any case such an aristocratic notion would not survive the widening franchise in the nineteenth century. When a democracy of the many overtook a republic of the few, the many wanted to be heard. Political parties thus channeled energy and anger into nonviolent change. They gave an outlet for the ambitious to guide their striving into a process which could restrain them.

Yet political parties are not an unmitigated good. Put reasonable and empathic people into a group, and the group can be anything but. Madison knew this (not that it stopped him): "In all very numerous assemblies, of whatever characters composed, passion never fails to wrest the scepter from reason. Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob."

Washington, by the end of his second term, had seen the danger of divisions. But what to do? In his Farewell Address, he warned: "[I]t is substantially true that virtue or morality is a necessary spring of popular government." We can neither suspend moral values nor our reason if we want parties to produce benefits without endangering liberty.

Morality is not enough, twisted as it gets in service to political ends. Since the framers did not envision political parties, the only constraint the Constitution provides is to divide power and establish checks and balances. Still, one party can dominate all three branches, concentrating power and fatally weakening opposition. This nearly happened under Jefferson. By the end of his second term, the Federalist Party almost ceased to exist, though Jefferson's effort to impeach Supreme Court justices failed.

The men who railed against "party" created the Virginia Dynasty (Jefferson, Madison, Monroe) that ruled for a quarter century, even though they lacked the modern tools of communication, fundraising, organizing, and gerrymandering that exist today.

The benefits of parties are real; so are their dangers - which are still largely unrestrained.

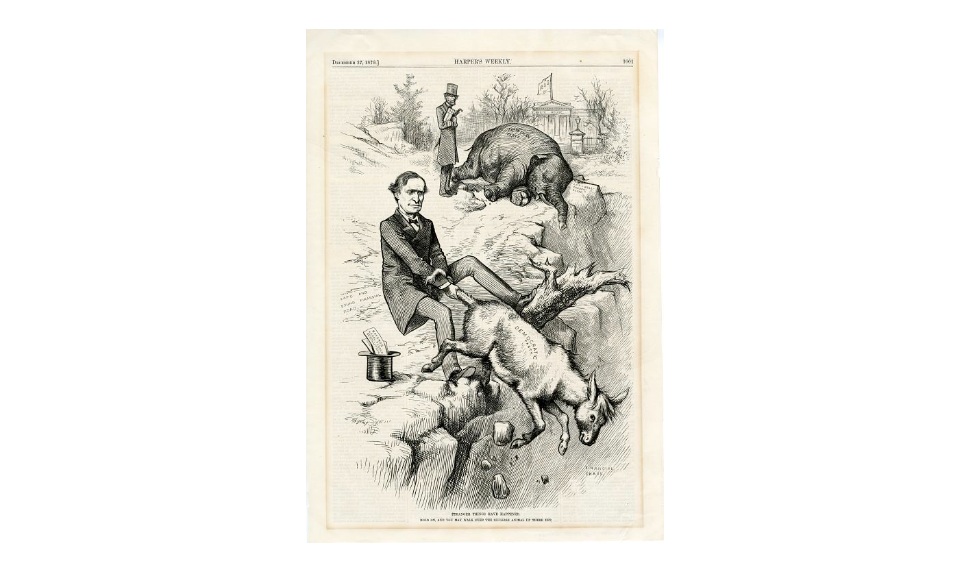

Photo Credit: Smithsonian Institution - First Cartoon Depiction of Symbols of Both Parties, by Thomas Nast in 1879