Understanding Our Constitution: #3 - The Majority Party Rules??

In his 1801 address, Thomas Jefferson reminded Americans that his election, "being now decided by the voice of the nation . . . all will, of course, arrange themselves under the will of the law, and unite in common efforts for the common good." Jefferson, a Republican, had just won the presidency after a vitriolic election during which passions led to threats of insurrection if he was denied victory by the Federalist opposition. Not surprisingly, Jefferson was reminding that opposition he had the right to govern, being elected by the majority.

Yet his next sentence tempered that mandate: "All, too, will bear in mind this sacred principle, that though the will of the majority is in all cases to prevail, that will to be rightful must be reasonable; that the minority possess their equal rights, which equal law must protect, and to violate would be oppression." Though historians debate how sincere Jefferson was, both sentences say something important about the Constitution.

In recent years, whatever political party controls the White House or Congress demands acceptance of their right to govern and acquiescence to their policies. The view that the Constitution gives the majority party a mandate is widely cited but not quite correct.

First, there were no political parties in 1787. In an act of myopia among otherwise farsighted delegates, the framers did not anticipate them. The very idea of organized political parties, who might sacrifice the common good to selfish ends, was abhorrent. Second, while the Constitution established majority rule, it was afraid of it. Under a king, a group that gets out of hand can be swatted down by the palace guard. In republican government, who can stop a tyrannical majority - especially if it corrupts elections and the courts?

After 1783, the newly independent nation faced a daunting problem. Historically, revolutions ended in despotism or mob rule. When Washington relinquished command of the Continental Army, he prevented the former. But the latter danger persisted.

The Constitution's solution was to allow the majority to govern but to make majority rule difficult. Power would be divided, first between the national government and the states and then among the three parts of the national government (and in Congress between the House and Senate). As Madison put it: "[A]mbition must be made to counteract ambition." The framers sought not to avoid conflict through giving the majority an unhindered right to rule but to create and manage conflict to prevent majority tyranny.

Citizens bemoan the partisan battles that result, the gridlock, a cumbersome government that takes forever to make decisions and longer to implement them. Yet this inefficiency was consciously designed into the Constitution.

The framers' wanted energy in government but restraint on government. That is what Jefferson expressed. The desire then - and now - is to win elections. The danger is that winners fail to balance their power with responsibility, that they pay insufficient attention to preserving the very system that enabled their victory.

What the framers called the "American experiment" relies on this balance. If power is used to oppress the minority, then majority rule slides towards tyranny. This fact of our Constitutional heritage is easily forgotten by today's talk radio, cable channels, interest groups, angry demonstrators, and partisan extremists - all intent on winning at any cost. Yet if they get all they demand, they will destroy the very system that enables their freedom.

What "responsible power" looks like will always be subject to argument. Yet it is not hard to conclude that, at a minimum, actions of a ruling majority should discourage extremism, encourage compromise, assure unfettered access to the ballot, build respect and trust in the democratic process, strengthen the civic and governmental institutions that foster reasoned dialogue, and prevent extreme concentrations of wealth and power that pollute the public square.

In his First Inaugural, referring to the nascent political parties then forming, Jefferson also reminded his country that "every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle. We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists." Rhetorical flourish, quite likely. Essential to preserve republican government, undoubtedly.

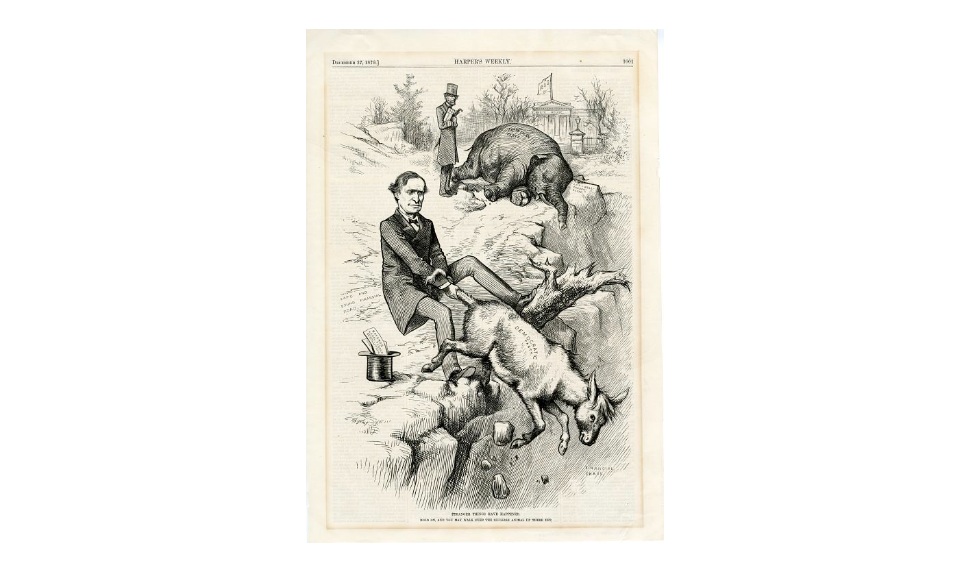

Photo Credit: League of Women Voters