Status Concerns Can Make for Sloppy Thinking

In December, 1978, United Airlines flight 173 crashed on final approach to Portland International Airport. The plane simply ran out of fuel because the crew was pre-occupied with diagnosing a landing gear issue. A major NTSB conclusion: the captain did not respond to concerns from the crew and they were reluctant to question his authority. Status differences in the cockpit killed ten people.

Status differences are ubiquitous. We relish talking about who's up and who's down. Those on top don't like to be challenged. Doctors don't like to be questioned by nurses, supervisors balk at pushback from employees, parents get angry when children don't stay in their place. Those low in status often resent it and strike back - verbally and sometimes physically. A multi-year study of "air rage" found that it's higher in coach if the plane has a first-class section and higher still if coach passengers have to walk through first-class to get to their seats. Being physically reminded that you're less than "first class" pushes low-status buttons, exacerbated no doubt. when they close the curtain between first class and coach and cram people into small seats with almost no legroom. Unable to vent their frustration on those above them, some take it out on their fellow coach passengers.

Our concern with status is hard-wired. Social psychologist Naomi Eisenberger had adults play "cyberball," a computer game in which three people toss a ball to each other. The subject sat in front of a computer screen and was told two others were doing the same in other rooms. The "two others" was actually a computer program. For a while, the ball got tossed among all three, but then the subject was excluded. Eisenberger used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to see what parts of subjects' brains activated. The results: regions associated with physical pain and disgust. It's no surprise, then, that people who feel socially ostracized say "you hurt me" and get angry. Yet the subjective feeling about status is not just where you are in the hierarchy but how you're treated in relation to how you think you should be. Even world leaders and corporate titans lash out when their higher status is not appreciated enough.

Researchers at NIMH and in Japan found other brain regions involved. In a series of games, again using fMRI, they found the striatum (associated with processing rewards) and the amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex (both associated with emotions) react when people feel their status is threatened but also when it has been enhanced. Combined with Eisenberger's work, the message is clear: the brain's first reactions to how we see our status in relation to others is emotional, not logical.

When status is threatened, emotion pushes reason aside. We don't think as clearly. We may become socially if not physically aggressive. Instead of collaborating (e.g. for a safe cockpit and a calm coach section) we may clam up or strike out. Silencing oneself is, after all, one way to avoid the pain of rejection.

Yet we don't have to react in these ways. Eisenberger found that, after a delay, the logical part of the prefrontal cortex can kick in, tamping down emotional hurt by putting things in perspective. Players can realize it doesn't matter all that much if they get the ball tossed to them. When the logical part of the brain operates along with the emotional part, thinking and decisions improve.

A study of 137 hospitals in England found that when staff are enabled to question authority if they see something that may harm a patient, mortality rates drop significantly. The crash of flight 173 sparked the development of "Crew Resource Management (CRM)," in which cockpit crews are trained to communicate as a team and question the pilot without challenging his or her status. CRM has spread to aircraft design, manufacturing, maintenance and air traffic control, all venues in which status concerns must be overcome to ensure safety. CRM is also practiced in some hospitals, EMS, and fire services teams.

Whether you're a worker, teacher, student, parent, partner, or friend, you care about your status. Whether you want to admit this, your brain does. So, don't forge ahead just because you feel challenged. Quiet your ego - take a physical and mental "time out." Step away from the situation, if only for a minute or two, to give yourself a chance for logic to engage. If you're the higher status person, show empathy for those below. Raise their status by making them comfortable and telling them how you value them. This can prevent social pain and lead to better communication, thinking, and problem solving.

Status differences won't go away, but the problems they can cause are not inevitable.

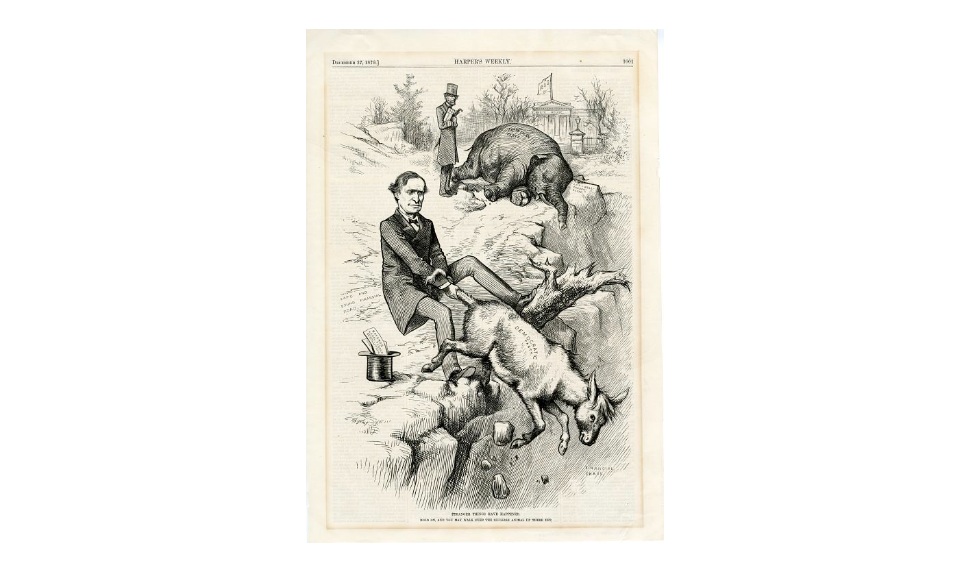

Photo Credit: Sustainable Economics