A Constitution Day Reflection: The Ongoing Challenge of Democracy

On September 17, we celebrate the 237th anniversary of the signing of the Constitution, what most Americans consider the founding document of our democracy. "Democracy is worth dying for, President Reagan said on the 40th anniversary of D-Day, “because it's the most deeply honorable form of government ever devised by man."

This sentiment is American canon. But it was not to Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts who, at the Constitutional Convention, intoned that "the evils we experience flow from the excess of democracy." It would also have surprised John Adams who said in 1814 that "democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes, exhausts, and murders itself."

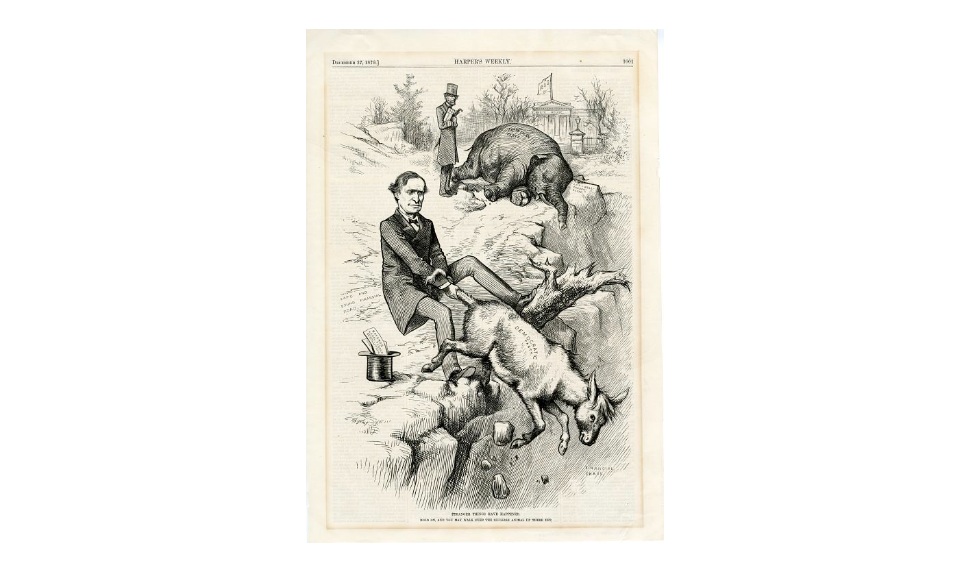

Many of the framers feared democracy? In Federalist #10, defending the Constitution during the ratification debates, James Madison argued that “[D]emocracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention . . . and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths." His chief objection was their proneness to demagogues and "factions" that would push self-interests at the expense of the "aggregate interests of the community." Since majority rule would govern, not a king, what could restrain a tyrannical majority? This is what many at the Convention saw in state governments - and why they sought a national government that could rein in democratic abuses.

The Constitution’s solution was to create a republic, a government by representatives not the people themselves. As Madison put it, this would allow government to "refine and enlarge the public views, by passing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens, whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of their country, and whose patriotism and love of justice will be least likely to sacrifice it to temporary or partial considerations."

Who would elect what Madison called “enlightened statesman”? Members of the House would be elected by voters, but at the founding these were white men of property. They were assumed to be prudent because land ownership reflected a stake in society. Senators would be elected by state legislatures, who would also control the selection of electors for president, in both cases isolating these choices from the “mob.” To further bolster the independence of Congress from the people and the states, the Constitution gave members longer terms than were typical in state legislatures, rejected term limits and the ability of voters to bind their representatives with instructions on how to vote. Supreme Court justices would have lifetime appointments, and all federal officials would be paid from the federal (versus state) treasury, giving them financial independence.

The republic the framers created in the Constitution has since become a democracy (or as some describe it a democratic republic). Egalitarian passions released by the Revolution overcame what many considered the Constitution’s anti-democratic provisions. The franchise has been extended to all citizens at least 18 years old. Senators are now chosen directly by voters, who also choose electors for president.

In short, we have the democracy the founders hoped to avoid. In many ways, that's been a good thing. The racism, sexism, and elitism of the founding generation have been weakened, though this is still a work in progress. The energy released by expanded franchise has expanded personal freedom and promoted commercial growth, material choice and other benefits that undemocratic nations struggle to achieve.

Still, the framers’ worries should not be ignored. Demagogues now have powerful tools to sway passions against the nation's long-term interests. Legislators dependent on extreme voters too easily succumb to, rather enlarge or filter, public views. Appointments to the Supreme Court have turned partisan and elected state court judges are much less independent of popular passions.

The framers rightly worried about “tyranny of the majority,” but democracy today is also subject to “tyranny of the minority.” Essentially unregulated campaign contributions give a few very wealthy people access to the highest rungs of power. Information technology makes it easy for a small minority to distort the truth and organize national campaigns that ignore majority views. Gerrymandered election districts permit extremist candidates to win elections merely by winning the small segment of those who show up in partisan primaries, effectively disenfranchising the majority of voters. The Electoral College enables a candidate to win the presidency though losing the popular vote, even by millions.

On Constitution Day, we should remember that government is administered by human beings, prone to selfish interests. No combination of Articles and laws guarantees a democracy will be just. A democracy requires civic virtue, a topic on which the Constitution is silent. Writing to Mercy Otis Warren on April 16, 1776, John Adams understood this:

“Men must be ready, they must pride themselves, and be happy to sacrifice their private Pleasures, Passions and Interests, nay, their private Friendships and dearest Connections, when they stand in Competition with the Rights of Society.”

“But I have seen all along my Life Such Selfishness and Littleness even in New England, that I sometimes tremble to think that, altho We are engaged in the best Cause that ever employed the Human Heart yet the Prospect of success is doubtful not for Want of Power or of Wisdom but of Virtue.”

Photo Credit: The Constitutional Convention, geralt-pixabay.com

(If you do not currently subscribe to thinkanew.org and wish to receive future posts, send an email with the word SUBSCRIBE to responsibleleadr@gmail.com)