Wonder-Full

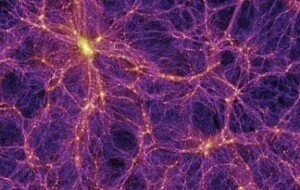

“Have a wonderful day!” We’ve all said this thousands of times. It’s a nice gesture, a caring way to say good-bye. To be honest, I’d never thought much about these four culturally polite words. Then I saw this image, recently assembled for the first time by astrophysicists, that captures the cosmic web, the filaments of dark matter and hydrogen gas that connect the universe. It fascinated me and led me to ponder what “wonderful” really means.

The Cosmic Web - Courtesy Project Sphinx

As a noun, wonder connotes something marvelous; as a verb, it means to speculate and question. So did I really wish others would experience something miraculous that invites questions – to have a day filled with wonder? Did I seek that when someone told me to “have a wonderful day”? Not if I’m honest. But that can change.

Since I have spent time lately learning about the brain, applying the literal (vs. cultural) expectation in “have a wonderful day” led me to another image that popped into my mind.

Neurons Firing in the Brain - Courtesy newstemple.edu

How curious – and intriguing - that what goes on in our brains mirrors in appearance what exists in the cosmos. Pushing a bit further, I found that the number of connections among the 100 billion neurons in our brain, connections that make possible everything we think and do, is estimated to be as high as 1,000 trillion. And that bears some striking similarity to the estimated number of stars in the known universe (200,000 trillion).

Thinking of the universe and the atoms within us led to two more images. Once again, the cosmos is not only out there but metaphorically at least in us.

Stars Rotating Around the Center of a Galaxy - Courtesy Hubble Space Telescope, NASA

Simulation of Electrons Rotating Around the Nucleus of an Atom - Courtesy: www.livescience.com

To take still another example of the power of wonder, only 5 percent of the universe is visible. The rest appears to us as empty space (though filled with invisible dark matter and dark energy). Our bodies also seem mostly empty space. If you compressed all of our atoms to get out the empty space in and between them, what’s left would fit into a cube less than 1/500th of a centimeter on each side. (So don’t worry if you’re very short (or very tall), there’s essentially as much of you as anyone else.)

Where did all our atoms come from? Nearly half have come from supernova (exploding stars) in the Milky Way – and the other half from supernova beyond our galaxy, carried by galactic winds as recent research has suggested. As the late astronomer Carl Sagan told us” “The cosmos is within us. We are made of star-stuff.”

Elements in the Body that Came from Exploding Stars - Courtesy: Natural History Museum, UK

Despite what we may think, then, we’re only partially earth-grown. Should I not then be more humble in how I view our place in the universe - and more grateful for its gifts?

There can be so much joy, complexity, confusion, and learning if we take the prosaic “have a wonderful day” into our hearts. How is it that 71 percent of the earth’s surface is covered by water and babies at birth are 78 percent water? Why do earthworms leave the safety of dirt to try, often so impossibly, to cross a cement sidewalk after it rains? Why are dentists more likely, statistically, to be named Dennis or Denise? Does laughing gas really make us laugh, and if so, why? Will the moon ever crash into the earth due to gravity? Why do we dream?

Understandably, many may view such ramblings about the cosmos and our bodies as just so much coincidence. After all, if you try hard enough you can find parallels among lots of things. But if Einstein can be awed by the cosmos and the sense of wonder it invites, can’t we as well? Is that what led him to the observation that “coincidence is God’s way of staying anonymous”?

I hope I never stop wondering. The questions are, in a major way, far more important than the answers. Our lives and the future of our planet depend on filling our minds with questions – and wonder. Civilization’s advances come from those who wonder. We desperately depend on wondering, especially among the young. They are our future. As Louis Armstrong put it in “What Wonderful World”:

“I hear babies cry

I watch them grow

They’ll learn much more

Than I’ll ever know

And I think to myself

What a wonderful world”

So, have a wonderful day!

Photo Credit for Title Photo: NASA.gov