West German Chancellor Willy Brandt Kneels at the Monument to Heroes of the Warsaw Ghetto, December 1970

(Credit: Sven Simon)

For years after World War II, many Germans considered themselves the conflict’s worst victims. Especially in West Germany, as philosopher Susan Neiman chronicles in her book Learning from the Germans: Race and the Memory of Evil, they considered the Nuremburg War Crimes trials as “victor’s justice,” not an indictment of their nation’s crimes. This warped historical memory retarded the growth of democracy in post-war Germany and slowed reconciliation with other nations, especially Israel. Neiman argues that failing to accurately recall and face the past is morally wrong, poisons the present and prevents a better future. Germany finally addressed this challenge (as demonstrated in small part by Willy Brandt’s apology) through its program of Vergangenheitsbewältigung, “working through the past”. Democracy in Germany is now vibrant and its children are taught an accurate history of its Nazi past.

Americans face a similar challenge in forming and acting on an accurate memory of slavery and its impact on our times. Indeed what Americans say they remember about slavery and our founding period differs and still plagues the present. Since no one today lived through that period, we draw on memories shaped by parents, relatives, schools, friends, films/books, politicians and social media. For example, the “1619 Project” of the New York Times sought to chronicle slavery and its impact on America. It contends with the “1776 Commission” created by President Donald Trump, which sought to promote “patriotic education” and end efforts that "vilified [the United States'] Founders and [its] founding." Until Americans “work through the past” of the memories they hold, we face continued social and political conflict. The protests of the Black Lives Matter movement and the counter protests of its opponents in recent years demonstrate the power of memories to shape how citizens think and act.

The Twin Towers on September 11, 2001

(Credit: National Park Service)

We all have historical memory, but that doesn’t mean our memory is accurate. Almost every American over 30 remembers where they were and what they were doing on the morning of 9/11 when terrorists flew planes into the Twin Towers. A 2009 survey showed we’re also pretty confident in our memories. Sixty-three percent of respondents said “human memory works like a video camera, accurately recording the events we see and hear.” Almost half (48 percent) said that “once you have experienced an event and formed a memory of it, that memory doesn’t change.”

Psychologists Jennifer Talarico and David Rubin actually tested peoples’ memories of 9/11. On September 12, 2001 they asked a group of Duke University students to complete a questionnaire about how they first heard of the attacks. Then, 1, 6 or 32 weeks later, they asked the same students to recall that event again. Comparing later recollections with the first ones, they found memories became more inaccurate over time. Yet, when asked, the students were very confident in their most recent recollections.

If we can’t agree with our own memories over time, yet remain confident they’re accurate, that’s a challenge to being a thinking citizen. Not only may our memories be wrong, but we’ll end up arguing with others who, like us, are overconfident about what they remember. When groups share and strongly defend a collective memory, arguments can turn into political battles. Gun rights proponents recall the Second Amendment was ratified to protect an unrestricted “right to bear arms”. Gun control advocates recall that it was only intended to ensure “a well-regulated militia.” Evangelical Republicans insist we began as a Christian nation. Liberal Democrats insist the Constitution enshrined the separation of church and state.

Solving this problem requires understanding how we form memories, how we forget and what to do about it. (It also requires avoiding some other thinking traps, such as information overload (Question #3) and overconfidence (Question #6)).

How Do Memories Form?

There are three types of memories:

1. Semantic memory: the recall of words and facts, such as the date for the next election or a website password.

2. Episodic memory: the recall of events, such as a street protest or last summer’s family reunion.

3. Procedural memory: the ability to repeat physical routines, such as riding a bike or using a voting machine, without having to think about every muscle movement.

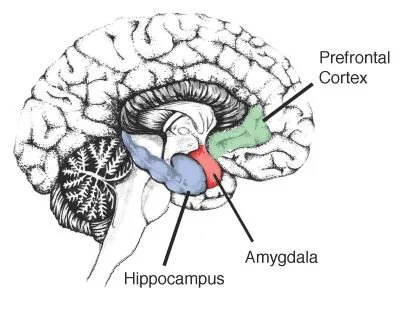

Our primary concern is with semantic and episodic memory. Both involve three brain regions.

Brain Regions Central to Memory

(Credit: guardianlv.com)

Memories are “recorded” first in the prefrontal cortex. A semantic memory, such as the name of someone you just met, usually will last in short-term memory for about 20-30 seconds, unless you keep repeating it. With repetition, the connections between the neurons that “record” the memory strengthen and it gets stored for the long term, first in the hippocampus. Episodic memory, since it’s in the form of a story with emotions – like your senior prom - engages the amygdala, the emotional center of the brain. The amygdala strengthens that memory as it puts it in the hippocampus. The stronger the emotions connected with the event - such as in personal loss or trauma - the greater the activation of the amygdala and the stronger the neural connections get.

A study of London cab drivers illustrates how this works. To get a license to operate a taxi, applicants must pass “The Knowledge” – a test showing they’ve mastered all 25,000 of the city’s streets as well as major landmarks, hotels, restaurants and routes to them. The study showed that the back of the hippocampus (which handles spatial memories) of those who passed the test increased in size compared to both those who failed and a control group. More neurons and connections were created to store more information. After the drivers retired and those detailed memories faded, that part of the hippocampus returned to normal size.

Forming a memory is the first step. To be useful, we must recall it, and that’s where things get tricky.

Fact Finder

How is it possible to sing the words to a song that you first heard years ago but have not heard in many years?

What Causes Faulty Memories?

Let’s Talk

Write down your memory of an important conversation you had with someone where you disagreed. Where and when was it? What was it about? Who said or did what? How did it end? Then ask that person what they remember about it? Finally, compare these memories. Were they exactly the same?

Lots of things make memory recall imperfect.

We Forget

Sometimes we just forget. Our brain’s storage capacity is limited. Who could possibly remember everything said in a presidential debate? Why would we want to remember the phone numbers of everyone we might call? Some neuroscientists postulate that we have “forgetting cells” which erase unimportant memories. The brain also forms new neurons, and these can “overwrite” exiting ones, weakening the connections that previously existed forming a memory. Researchers have also identified “extinction neurons” that suppress bad memories, such as traumatic incidents. Psychologically, it may be a good thing that we can forget some bad memories; otherwise it would be hard to face the future optimistically.

We Have the Gist of a Memory, Not an Exact Reproduction

The hippocampus, like a computer hard drive, has limited storage capacity. To solve this problem, many memories get consolidated while we’re sleeping and sent back to the prefrontal cortex, where they await our need for them. Yet this process of consolidation and transfer doesn’t always store the memory exactly as first formed.

Look at this drawing of a bathroom:

(Credit: Neuropsychologia)

Now cover the drawing and continue reading.

Which of the following items did you see in the bathroom? - toilet, sink, scale, mirror, plunger, shampoo bottles, shower head, toilet paper, rubber duck, Windex bottle, flowers in a vase?

Research by Christina Webb and colleagues shows people tend to recall seeing the sink, toilet paper, scale and/or plunger even though they were not in the drawing. We’ve all seen many bathrooms. Our brain cannot store every image of every bathroom so over time what gets stored in long-term memory is the concept of a bathroom as having certain items – even if some bathrooms lack them. In other words, our memory is not a perfect reproduction but a reconstruction of prior memories. As the authors conclude, we form the gist of a bathroom – as we might recall the gist of a presidential campaign or a community meeting - even if some of what we recall is wrong.

During the health care debate in 2009 that led to the Affordable Care Act, some criticized President Obama for refusing to meet with Congressional Republicans to forge a compromise. That criticism was based on many images they saw of the president alone and of his opponents alone. Even though he met with Republican leaders several times, most covered by the media, the gist stored in many people’s memory of “the Obama health care process” left that out.

Space Shuttle Challenger Explodes 73 Seconds After Liftoff

(Credit: NASA)

We Have Faulty “Flashbulb” Memory

As we saw with 9/11, “flashbulb” memories occur with very emotional events and convince us we capture them perfectly, like a camera would. The day after the Challenger space shuttle blew up on January 28, 1986, Eric Neisser and Nicole Harsch asked participants to describe their recollection of it. Participants’ descriptions were compared to their account two-and-a-half years later. Twenty-five percent of participants were wrong in every detail when the later memory was compared to the initial one. Fifty percent were wrong in two-thirds of the details.

This problem shows up in eyewitness testimony, which is the most frequent reason those exonerated by DNA evidence were originally convicted. What people recall about an alleged perpetrator when they later identify a suspect in a police lineup and on the witness stand is often inaccurate.

Eyewitness Identification, Which Relies on Memory, Can be Unreliable

(Credit: The Innocence Project)

Why does this happen? Every time we remember, we reconstruct that memory anew, often combining elements of other memories stored in the brain. In fact, the brain has to do this. As David Linden notes in Unique: The New Science of Human Individuality:

“For memory to be useful, it must be updated and integrated with subsequent experience, even if it alters the memory of the original event… In most situations, a generic memory compiled from many trips to the beach is more useful in guiding future decisions and behavior than fifty stand-alone, detailed, and accurate beach trip memories. The repetition-driven loss of detail allows for the efficient use of the brain’s limited memory resources.”

Fact Finder

Does memory worsen as we get older?

We Can Be Motivated to Forget

“How can you not remember that?” is an expression most of us have used in talking with someone. Sometimes, however, we want to forget things. We may do so because it’s psychologically comforting. Perhaps we don’t want to remember something we’re not proud we did. In one study college students were asked to recall their high school grades. When researchers compared their memories with their actual grades, 29 percent “forgot” they got any “D’s” in high school.

This is motivated forgetting. One simple illustration of motivated forgetting came in the aftermath of President Kennedy’s assassination in 1963. Sixty-four percent of people in a poll remembered voting for him, although he won the election by the razor-thin margin of 49.7 to 49.6 percent of the votes. Apparently, people prefer having picked the winner.

(Credit: Americans for Tax Reform, atr.org)

In 1985, Grover Norquist launched Americans for Tax Reform. As a way to pressure politicians to prevent tax increases, he asked them to sign “The Pledge” that they would abstain from almost all tax increases. Four decades later, “The Pledge” still exerts a powerful influence, especially in the Republican Party. The Pledge came in the midst of Ronald Reagan’s presidency as a way to help him cut taxes, and Reagan is viewed as a model for doing just that.

Reagan did cut the top income tax rate from 70 percent to 28 percent and also boosted business tax deductions. But he also increased taxes. He broadened the tax base by making it harder to avoid paying taxes and by closing tax loopholes. He accelerated an increase in the payroll tax for Social Security, required higher-income earners to pay taxes on some of their benefits and required the self-employed to pay the full Social Security tax rate not just the part those employed by organizations pay. The result of his measures was that federal tax revenues actually were 0.1 percent of GDP higher during his presidency than the preceding 40-year average.

Remembering all this today can be inconvenient, however, if President Reagan is your model of tax cutting. It’s easier to forget the tax hikes. That’s motivated forgetting.

Memories Can Be Implanted

The opposite of forgetting something is remembering something that never happened. In public affairs, that’s one of the dangers of misinformation or “fake news.” When people act on such “implanted memories,” rational thinking is impossible.

In the week before a 2018 Irish referendum on legalizing abortion, Gillian Gage and her colleagues at University College Cork recruited 3,140 eligible voters. After asking them whether and how they planned to vote, they gave each six news stories about the issue and asked them to read the stories. Two stories were fake – one each depicting advocates on either side of the issue using illegal or inflammatory behavior. Participants were then asked if they had heard about the event covered in each story and if they had specific memories of it.

Almost half of the participants reported a memory for at least one of the fake story events. Some even recalled details that were not in the fake story. Interestingly, those in favor of legalizing abortion were more likely to remember fake news about their opponents, and vice versa. Finally, even when participants were told some of the stories they’d be given were fake, many refused to reconsider their memories of the fabricated events. In short, fake news was implanted as true news in their brains.

Let’s Talk

Why do public figures try to shape our memories of American history on such things as the causes of the Civil War?

Social Groups Can Foster Faulty Collective Memories

In pre-war Nazi Germany, Adolph Hitler sought to shape citizens’ memory of what led to its defeat in World War I. He argued that its army was “stabbed in the back” by politicians and Jews. Through extensive propaganda and the force of his rhetoric, he rose to power through gaining widespread acceptance of this faulty history. Groups can form collective memories - shared pools of memories, knowledge and information that forge the group’s distinct and desired identity. Collective memories are powerful because they satisfy psychological needs. They reduce anxiety and ambiguity in an uncertain world by offering narratives of “who we are, where we’ve come from and where we need to go”. They give their adherents feelings of belonging and self-esteem (even at the cost of differentiating “us” from “them”).

Faulty collective memories can be very resistant to correction. In an experiment at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, participants in a small group were shown a 45-minute video about illegal immigrants and their interactions with police. After watching the video, each participant, on a computer, took a 200-question test about details in the film. Days later, participants came back and took the test again, this time while they were being monitored with an fMRI scanner that showed what parts of their brains were most active. But before answering each question, a participant was shown how others in their small group answered. Some of those group answers shown to the participant were purposely wrong.

Finally, after the second administration of the test, participants were told that some of the answers given by others in their group were faked. Then, participants were asked to take the test a final time and answer based on their own memories. Half of the participants stuck with the fake answers – but denied they were influenced by others.

What the fMRI showed was that the amygdala reacted when participants were told of others’ answers and this led to changing their previously stored memory in the hippocampus. In short, being part of a group – and being influenced by a group – can permanently transform initial memories. (In Question #13, we focus more on how group pressure shapes political views.)

So What? Now What?

Thinking citizens need to stay alert to these thinking traps:

The gist memory mistake: we store the concept of something and so we may get some details of a memory wrong

Belief in flashbulb memory: we’re overconfident of our memories of emotional events

Implanted memories: “fake news” creates “memories” of things that never happened

Collective memories: shared pools of memories, knowledge and information can forge a group’s distinct and desired identity and be resistant to change

Several strategies can help avoid these errors as we engage in public affairs.

Be Humble: It’s a candid acknowledgement that we’re human and our memory is often imperfect. Just acknowledging this opens us to other steps we can take. At the same time, refusing to acknowledge the possibility of error chokes off any chance for correction and can stymie conversation, collaboration and compromise.

Test Your Memory: During the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, President Kennedy and his advisors continually questioned what they recalled and knew about the situation and its history. All public issues have antecedents – events, people, information, organizational actions – that must be accurately recalled in current efforts to solve a problem. As recounted by historians Richard Neustadt and Ernest May in Thinking in Time: The Uses of History in Decision Making, Kennedy and his advisors adopted a practice the authors labeled as stating what is “Known, Unclear, and Presumed.” Every piece of information we might act upon can be placed in one of these categories. In regard to memories, what is known are things that have been verified by other, unbiased sources.

But what is unclear or presumed must be researched, verified and/or tested. Memory errors can easily occur with some things are unclear or presumed. As they note, this is especially true when using an historical analogy in current decision making. Some people now call for a “Marshall Plan” in the Middle East, recalling correctly how this major financial and diplomatic commitment helped revive the European Economy and save Western Europe from communism after World War II. Yet their memory of the Marshall Plan forgets that France and England, for example, had functioning democratic governments, good civil institutions and a commitment to secular government – all of which helped the Marshall Plan work but do not hold true for countries such as Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria and Lebanon.

“Remember my friend that knowledge is stronger than memory, and we should not trust the weaker” - Bram Stoker, Dracula

Monitor the Sources of Your Memories: One way to check the accuracy of a memory is asking: what’s my source for it? Misinformation campaigns thrive on implanting information that we later remember, though we can’t recall where that information came from. This is called the “sleeper effect” since it divorces the information from the source so we no longer question how accurate and credible it is.

Civil War Casualty

(Credit: commons.wikimedia.org)

Recovering sources is very important when public issues require correct recall of history. Over 150 years since it ended, Americans still disagree on the cause of the Civil War. Some remember it as a war over slavery. Others remember it as a war over states’ rights. The accuracy of these memories has a powerful impact on public policy issues such as education (what do we teach?), poverty (why does generational poverty persist?), and voting laws (is discrimination still present?). Yet with many such strongly held memories, we’d have a hard time identifying our sources. We just “know” we’re right. Yet we can search for those sources – and for new ones - to verify or correct what we “remember.” This requires humility, of course, and searching books and websites and engaging in conversations with those who may challenge our memory can be very helpful. The fact that others have a different memory of the same thing is a sign that we may need to work harder to make sure a memory is accurate.

Engage the Prefrontal Cortex: In the Weizmann Institute experiment discussed earlier, many participants didn’t allow the group’s responses to alter their memories. The researchers found that in these cases, the brain scans showed they had a very active frontal lobe, the part of the brain that engages in critical thinking which can over-ride emotional responses. To make sure you engage your frontal lobe when recalling memories, several steps may be useful: (a) acknowledge that group pressure can play a role; (b) actively limit the power of your emotions, such as by separating from a group and finding a quiet time/space to focus on your memories, and (c) use critical thinking skills (e.g. testing assumptions, fact-checking) to question and revisit the source for your memory.

“Faced with a choice between changing one’s mind and proving there is no need to do so, most everybody gets busy on the proof.” – Economist John Kenneth Gailbraith

Challenge Collective Memories: Avoiding the seductive danger of a collective memory requires a willingness to face the factual history of an issue or event. History requires objective, unbiased evidence. History emerges from debate among scholars who contest each other’s conclusions. Collective memory avoids debate. History fights the tendency of groups (even groups of historians) to cling to accepted narratives. Collective memory demands uniformity. Facing the truth requires a willingness to admit to error. Research shows that we can test our collective memory by searching for information we don’t ordinarily see, such as asking others with different memories what evidence they draw upon or consulting more varied sources of factual information.

Use the Brain to Maximum Efficiency: As we saw in Question #3, our brain has limits, so:

o For Remembering Facts and Words (semantic memory): keep written records on your computer, phone, or in files of things you want to make sure you can recall accurately thus eliminating the need to store them in your brain.

o Chunk information into smaller segments. Remembering a 10-digit phone number is hard, which is why most are presented in three chunks: xxx-xxx-xxxx.

o For Remembering Events (episodic memory): you can rely on taped recordings and other sources (e.g. news accounts, YouTube videos, a journal you’ve kept). Be sure to consult a variety of sources.

o For Enhancing Memory of All Types: Regularly get a good night’s sleep, since it is during sleep that memories are consolidated in the hippocampus.

o Avoid Distractions: Research also suggests that you’re more likely to remember information if you’re not distracted while you are experiencing it. So pay undivided attention on what you really want to remember. Avoid multi-tasking (see Question #3).

Questions #5-8 have dealt with how we can think effectively about public issues – how we can make up our minds. But what if that requires us to change a long-held view? How easy is it to make a real change in what we think? That’s the focus of Question #9.