(Credit: John Tyson - unsplash.com)

At the height of the debate about President Biden’s $1.9 trillion COVID relief bill in late February 2021, 46 percent of Americans polled by Monmouth University said they had heard only “a little” or “nothing at all” about it. Yet 96 percent either supported or opposed it. In short, a lot of people took a stand even though they admitted not knowing much about it. This is no doubt true on other issues. Americans have lots of positions on such complex topics as policing, immigration, the deficit, guns and economic policy. Indeed, your friends as well as pollsters will press you to state your opinion: “well, what do you think?”

But what if you don’t know what you think? Can you just say “I don’t know yet”? Yes - and you should if you have not been able to study an issue and reach a thoughtful conclusion. Just because others have an opinion – and may press you to share it – doesn’t mean you have to do so.

“I can live with doubt and uncertainty and not knowing. I think it is much more interesting to live not knowing than to have answers which might be wrong … In order to make progress, one must leave the door to the unknown ajar.” - Richard P Feynman, American physicist

Our felt need to reach conclusions on what we think about public issues and politics in general can be managed by understanding several ways our brain works.

Let’s Talk

How much do you think Americans really know about poverty in America? Does what they know (or don’t know) affect politicians?

The Illusion of Knowledge

Even when we think we know facts needed to make a judgment, we may be kidding ourselves. On average, Americans believe 17 percent of the population is Muslim but it’s actually one percent. They believe 31 percent of the federal budget goes to foreign aid when it’s less than one percent. Asked in 2019 if a universal basic income of $1,000 per month for everyone 18 and older is a good or bad idea, only 8 percent were unsure, but it’s probably safe to assume most of the other 92 percent could not answer core questions such as how to pay for it and its impact on the incentive to work.

Inside of a Samsung Galaxy

(Credit: pcadvisor.uk.com)

Sometimes we just think we know more than we do or we rely on a mental model (see Question #4) that may be faulty. This is called the illusion of knowledge. We all know how a cell phone works, right? But asked to explain the parts, mechanics and how it connects to cell towers and the Internet, most of us would struggle. Until we try, we don’t know what we don’t know.

“The indispensable judicial requisite is intellectual humility.” - Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter

We can easily be overconfident about what we know. Managers in one study were given a ten-question test (e.g. how many U.S. patents were issued in 1990?). They were asked to provide a low and a high guess such that they were 90 percent confident the correct answer fell somewhere in that range. That is, they should be wrong just 10 percent of the time on the ten questions. The result: they were wrong 99 percent of the time. This is an example of the Dunning-Kruger Effect, named after two social psychologists whose research concluded that “not only do [people] reach mistaken conclusions and make regrettable errors, but their incompetence robs them of the ability to realize it.” Or, as French philosopher Michel de Montaigne put it, “the plague of man is boasting of his knowledge.”

Fact Finder

What are some more examples of the Dunning-Kruger Effect - things people are overconfident they know?

Information Bias

In the Internet age we can gather all kinds of information with which to make judgments on public issues. Type any subject in a search engine and the results are astounding. On “guaranteed basic income” Google delivers nearly 40 million hits. We can read as many as we wish. Doesn’t that help? Not always. We can fall prey to information bias, the psychological error that assumes more information leads to better decisions. Doctors, for example, bemoan patients who think they know enough to diagnose their medical problem and tell the physician how to treat them because “I researched it on the Internet.”

In one study by psychologist Paul Slovic, handicappers were given five pieces of data about each horse in a race. They picked the winner 17 percent of the time. Later, given 40 pieces of data about each horse, their success rate was no better - but they were much more confident about their picks! Having too much information can overwhelm our brains, making it impossible to turn information into wise choices. (That’s information overload – see Question #3). As T.S. Elliott put it in The Rock, “where is the knowledge we have lost in information?” Information is like temperature readings. Even if you had one from every city in the U.S., you would not necessarily be able to make a knowledgeable weather forecast.

Need for Closure

Look at this photo. What do you see?

If you’re like most people, one thing you see is a triangle. But there are no lines drawing a triangle; we just know it’s there. That’s the brain’s need for closure – we fill in what’s missing so we can make a decision. The need for closure shows up in many situations, prompting us to come to a conclusion or take a stand because we feel we must or someone is pressuring us to “make up your mind.” Closure, of course, can be very helpful. Without it, decisions would never get made and little would get done. Indeed, we often admire people who are decisive: “she’s a closer.” Closure is not the enemy; premature closure is.

In 2003, the Bush Administration insisted Iraq’s Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction (WMD), denied the United Nations more time to verify their presence and went to war. No WMD were found. At the onset of the Revolutionary War, George Washington wanted to attack Britain in full frontal assaults to push for an early victory. Yet his poorly trained army was no match for British regulars, leading to disastrous defeats. Washington eventually figured out pushing for closure was a mistake (he adjusted his mental model as a result of System 2 thinking – see Question #4). He didn’t need to win the war; he just had to make sure he didn’t lose it. So he avoided pitched battles of large forces, a delaying strategy that wore down the British until France joined the American side. The rest is history.

Let’s Talk

When have you been so sure of something and later found out you were mistaken? What did you learn from that?

Intolerance of Ambiguity

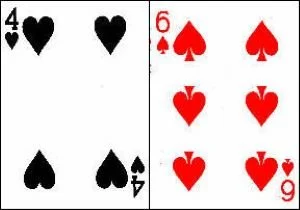

In a series of experiments, cognitive psychologists Jerome Bruner and Leo Postman briefly showed subjects playing cards such as these and asked them what they saw:

(Credit: www.staff.ncl.ac.uk)-

Ninety-six percent of subjects described these as normal cards, when clearly spades are black and hearts are red. When they allowed subjects more time, some insisted on their initial judgments and some were torn between what they realized they saw and what they had expected to see. They hated the ambiguity the confusing cards presented.

The notion of the intolerance of ambiguity was coined by psychologist Else Frenkel-Brunswik. Many people hate uncertainty because ambiguous situations can be stressful. Just think about how much anxiety you felt about COVID 19 not knowing what it was safe to do, if you would contract the virus and if you should get the vaccine. Ambiguity can propel the need for premature closure. It can also lead people to strongly defend the certainty of their conclusions and refuse to change.

The need for resolving ambiguous situations by coming to premature conclusions can lead to bad decisions. Brain research shows that the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex, two brain structures that deal with emotions, are more active when people are in ambiguous situations. When emotion overwhelms rational thought, trouble can follow. The surgeon, writer and health care researcher Atal Gawande put this emotional struggle issue in the context of medical care:

“The core predicament of medicine . . . is uncertainty. As a doctor, you come to find, however, that the struggle in caring for people is more often with what you do not know than what you do. Medicine’s ground state is uncertainty. And wisdom – for both patients and doctors – is defined by how one copes with it.”

What is true in medicine is certainly true in public affairs. Imagine your local community is considering whether to allow a cell tower to be constructed near an elementary school. Those in favor say it will improve service in current cell phone “dead zones.” Those opposed are concerned about how the radiation will affect children in the school. Some worry about the way it will mar the view in the landscape. The local cell provider assures everyone it will be safe and unobtrusive. But can you depend on a company with a financial stake in the decision? The town council is being pressed for a decision and is reluctant to drag this out while “we wait for more data.” What would you advise? There a lot of public issues with this kind of uncertainty.

Thinking citizens – and their elected and appointed officials – need to get more comfortable with ambiguity. Sure, they need to reach conclusions, but not too quickly, without careful thought and community input. Balancing the pressures of the moment and the need to think unpressured is a key task of citizenship.

Fact Finder

The United States escalated the Vietnam War because President Johnson concluded that North Vietnamese patrol boats had attacked two U.S. destroyers in the Gulf of Tonkin. Did they? What was good/bad about the decision process?

The Pressure of Other People

Delaying a political decision until you’ve carefully thought about it can be tough when you are subjected to pressure from family, friends or groups to which you belong. It’s stressful to say “I don’t know what I think” when everyone around you says they do. At the same time, it feels good to be accepted and appreciated for what you think, even if you don’t really know yet what you think. Be wary of such pressures, because it’s a human tendency to vigorously defend a decision once we’ve made it. (For more on the dangers of group pressure, see Question #13. For more on why we’re so reluctant to change our minds, see Question #9.)

So, What? Now What?

Thinking citizens stay alert to these four thinking traps that pressure them to take a stand on a public issue before they’ve had the chance to consider it carefully:

The Illusion of Knowledge - thinking we know a lot more about something than we do

Information Bias – thinking that more information will always lead to a better decision

The Need for Closure – making a decision because we feel pressure to do so

Intolerance of Ambiguity – making a decision because we can’t stand uncertainty

Thinking citizenship means resisting these traps. You can, of course, just say “on this issue, I’m keeping an open mind.” But there are several other steps you can take:

Practice Intellectual Humility. Research by Elizabeth J. Krumrei-Mancuso and her colleagues suggests that people who score higher on intellectual humility are less likely to exaggerate what they know, more likely to be intellectually curious, more open to finding new evidence and changing their views, have less need to come to closure and are less politically rigid. You can take and self-score her Comprehensive Intellectual Humility Scale to see where you are on this concept.

Sample Items from the Krumrei-Mancuso and Rouse Comprehensive Intellectual Humility Scale

Slow Yourself Down: If your need for closure is high (take the Need for Closure Scale to find out), reduce the pressure to decide. Develop an action plan to gain more knowledge on the subject. Set a timeframe further into the future to reach a decision. Let a tentative decision just sit there for several days so you can reduce the pressure for closure and certainty while you mull it over.

Structure a Good Decision Making Process: After the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion to oust Fidel Castro from Cuba, President Kennedy realized he had been rushed into a decision by a very flawed decision process. When Soviet missiles were discovered in Cuba the next year, his military advisors urged him to attack Cuba and bomb the missile sites. Yet he did not want to rush to a decision again. So set up a much more diverse group of advisors, gathered extensive information (accepting that there was a lot he didn’t know), created multiple options and tested the assumptions and the possible unintended consequences of each. He thus slowed down the rush to closure (though the missiles were just 90 miles from the U.S. mainland) to avoid group pressure and a premature conclusion. You can follow a similar approach. Consult people who have diverse views on an issue. Get input, as he did, from those who will not “go along to get along.”

“ . . . economists always wanted an economic solution, lawyers a legal solution, diplomats a diplomatic solution. Why should I be surprised the military wanted a military solution?”

– Special Advisor Ted Sorensen, commenting on the decision process during the Cuban Missile Crisis

Develop a Questioning Mindset: When COVID 19 struck, many government leaders rushed into massive shutdowns of public and private businesses and schools and issued stay-at-home orders. Then, when it appeared that things might be easing, they rushed to re-open. Both strategies proved seriously flawed because not enough questions were asked. Had policymakers asked such questions as what will result from shutdowns, how can we shutdown and open up sensibly, when should we take certain steps and why should we do this and not that, the results might have been better. Open-ended questions (the ones that often start with why, what, how, when) are powerful. They launch thinking into creative solutions. Clearly, decisions had to be made and fairly quickly, but a little patience can go a long way.

Let’s Talk

What are some ways you can say to people that you don’t have an opinion on an issue yet?

Revisit Your Conclusion About What You Know: Making a decision about a public issue because you know what you think may be a first step but should not be the last step. Say you’ve decided that nuclear energy should not be used to help end reliance on fossil fuels. You’ve read about nuclear accidents (Three-Mile Island, Chernobyl, Fukushima), the problems of storing nuclear waste safely and about the danger of terrorists gaining access to nuclear plants. Nothing you’ve seen has changed your mind, and those you’ve talked to agree with you. Still, you lose nothing by keeping your mind open longer. Look for contrary evidence. Talk to those who take the opposite view. Find out what new designs there may be for nuclear plants. Test your assumptions about the storage of nuclear waste. Then, and only then, revisit your thinking and see if your earlier conclusion still makes sense.

“It’s not what we don’t know that gives us trouble. It’s what we know that just ain’t so.”

– Humorist Will Rogers

One way of finding out what we know and don’t is to use the expertise of others. Question #6 explores how we can find true experts and how to judge the value of their advice.